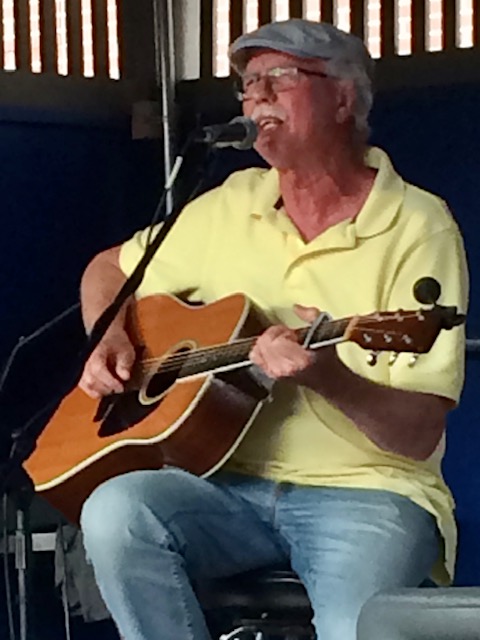

Note: House Rent Records is guided by a team of 10 people. Stan Unruh is one of these people and a dear friend of the House Jumpers.

I did not know of or hear secular music until Miss Noe, my grade school music teacher, introduced it in the early 1960’s. All I had ever known was live gospel singing with no instruments. My family and all my relatives were members of a Mennonite sect called Holdeman, and did not believe in secular music, or musical instruments, or any “worldly” media such as radio or TV. In the old country church we attended, the congregation raised their voices in harmony, singing the old hymns during a good portion of the services. The men on the right side of the aisle thundered out the bass and alto, while the women on the left side raised the high tenors and sopranos. It all blended as it echoed around the large high sanctuary. I loved it and spent the time during long sermons studying the hymnal and picking out my favorites. Sometimes the song leader would ask for a request, and my father would let me blurt out a song number. It felt powerful to hear the mix of voices I had commanded!

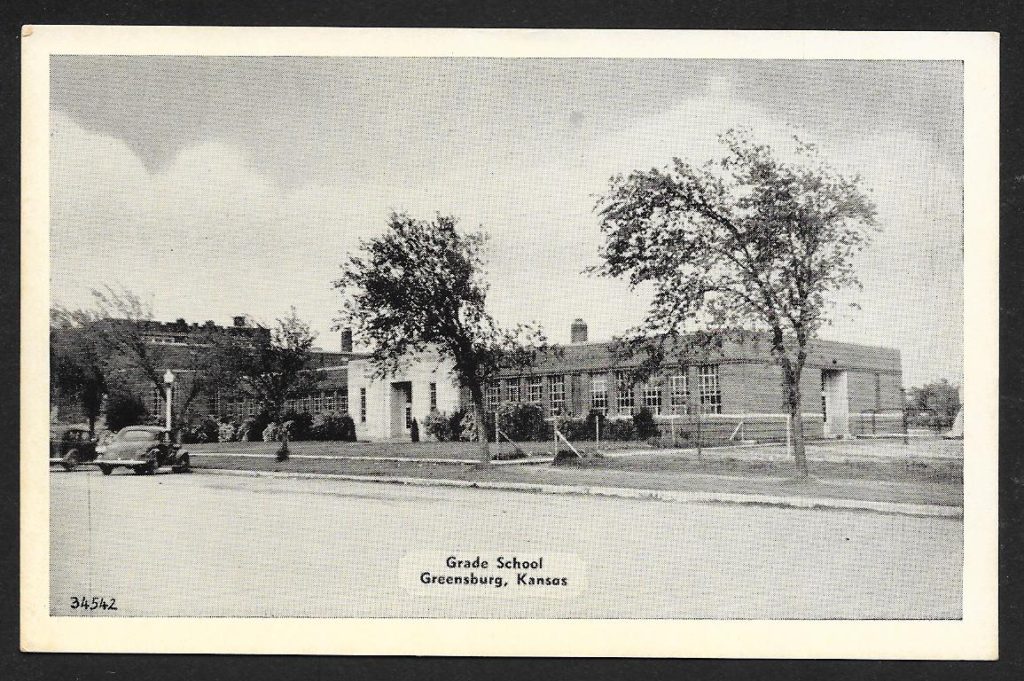

And then came 1960, and I reached the age that the government required all children to be in public school. The Mennonite leadership knew that public school was not always compatible with the simple ways of life they claimed to believe in. They were modern enough to understand the value of education for the sake of career training but would have preferred to leave the “nonsense and foolishness” out of it. That term was sometimes used to describe all other activities besides reading, writing, and arithmetic.

But despite all their grumbling, they were law abiding people. So it was that I found myself on a big yellow school bus with strangers, going to spend the day in a far different world than what I was used to. I was quite intimidated by the whole experience and pulled inward, I think. I managed to escape much of the unpleasantness and the feeling of not belonging by daydreaming, which gave the teachers the impression I was a “slow learner”. I was a slow learner mainly because my head was just not in the classroom.

One of the few bright spots at school was the “nonsense and foolishness” of music class. Miss Noe taught elementary music, and she stood out as a teacher. The Mennonite women I knew were passive, quiet, plainly dressed, and humble, and were aware of their lowered status. The seating arrangement in church underscored that status as they were seated separately to the left of the men. Miss Noe was the antithesis of those women. She would march into the room with her head high, wearing a tight red skirt, high heels, and red lipstick. She sat down at the piano (an instrument new to me) and pounded out the melody to a song, beamed at the children, and we all sang along.

The songs she taught us were not gospel hymns, but songs about the joy of the real and tangible parts of life. Songs about children playing on the sidewalks of New York, or lazily floating down the Erie Canal on a raft and being pulled from the shore by a donkey. Songs like Woody Guthrie’s inclusive message that stated, “This land was made for you and me”. The colorful illustrations accompanying the songs fueled my imagination about far away places in the distant past. Other songs were more reflective, like one from the perspective of an old gentleman roaming through an old grove of ash trees and remembering it from his childhood.

The friends of my childhood again are before me.

Each step wakes a memory as freely I roam.

With soft whispers laden the leaves rustle o’er me.

The ash grove, the ash grove alone is my home.

Other songs were sad, but in a way that touched something inside me that was at the same time joyful. “On Top of Old Smokey” evoked a wistful mood of a climber who remembered a similar climb with a lover now lost. I learned of the beautiful Shenandoah valley and felt deeply the regret of the author that the distant wide Missouri river was separating him and preventing a return to that magical place. And then there was this plaintive yearning from a wanderer of the western plains.

Don’t bury me, on the lone prairie.

Where the coyotes howl, and the winds blow free.

These songs spoke to the introvert and dreamer within me. They reminded me of the persistent Kansas winds and the waving grass in our pasture, and the loneliness and longing I felt. They reminded me of the grove of trees in the dry creek bed of our pasture where I would build tree houses and dream of flying my own home-made flying machine just over the treetops.

Later I learned that Stephen Foster was the author of many of the songs we sang. “I Dream of Jeanie With the Light Brown Hair”, “The Camptown Races”, “Beautiful Dreamer”, “My Old Kentucky Home” are songs I remember very well. My favorites of his were “Old Folks at Home”, and “Hard Times Come Again No More”. These were songs of longing, hopeful of a future joy once the hard times were gone.

I was by no means a favorite student of Miss Noe. I was too introverted and troubled by the feeling of not belonging to open my mouth wide and sing with joy like the other students. I refused to learn the complicated language of musical notes. They all looked the same, unlike the shaped notes in the church hymnal. I could sing the song, so why learn how to read the music?

For the most part I was frightened by Miss Noe and I avoided her contemptuous glare. But one day as I was leaving her classroom, she stood by the door wishing us all a good day. I was the last one out, walking slow with shoulders stooped and looking down at the floor to avoid eye contact with anyone; most of all her. Suddenly she called out with a stern voice, “Young man, come back here”. I did. She issued a string of commands. “Stand straight”. “Hold your head high”. “Put your shoulders back”. “Look straight ahead”. I did all those things. “Now walk”, she said. I walked down the hall feeling empowered and with a sense of wonder. It was so simple to pretend I was equal to everyone else. Who knew? All it took was one assertive person to give me permission.

I’m sure I regressed a lot, but I do remember reminding myself quite often to correct my posture and look others in the eye. The psychological effect of that simple action is amazing. I found that if I pretend to be equal, others assume it is true, and I guess I eventually started to believe it myself.

I wish I could locate Miss Noe today and thank her. I did a little internet search recently, but only found dead ends. Given our age difference, I suspect she may no longer be with us. If any teachers are reading this, my wish is that you realize the difference you can make in a person’s life without ever having a clue of the long term effect your example had on a student.

I sometimes consider myself unfortunate to come from such a repressive community. But I also consider myself very fortunate that I came of age during a time of progressive social change in the U.S. Public education was a mandate, and parochial schools did not exist for small religious institutions such as ours. But in 1972, the year I graduated High School, the Supreme Court ruled in Wisconsin vs. Yoder that religious minorities had the right to remove their children from schooling after eighth grade for religious reasons. A few years later, the church I grew up in built a country parochial school which went to 8th grade, and since then almost 100% of the children attending this school go on to become faithful members of that repressive sect.

Public school planted seeds within me that eventually flourished and choked out all the seeds of repression that had also been planted. The freedom to be who I am, the confidence that I am good enough, and a life-long love of folk music were the result of Miss Noe and other teachers who were simply promoting the values of our nation and humanity as they knew it.